Bare House, initiated and curated by Annu Wilenius [2009 – 2015]

During a two-month residency in Mongolia in 2009 I was asked to comment on the constructed environment. The project focused especially on architecture and the dimensions of personal existance; taking as a starting point, the core idea that, as much as we design our environment, these environments also design us.

Most of the Mongolians still live in gers (Mongolian round tents), which form the heart of the nomads’ culture. The gers are made out of feld. This is how I discovered my fascination for felt as building material. After the residence I made a sereis of carpets out of felt.

About Travelling

Each trip is different, but they are all based on the same rituals of transition: the departure, the passage and the arrival. For the exhibition in Ulaanbaatar, I wanted to focus on the influences the journey to Mongolia had on me. How do we deal with the memories we acquire when travelling? What remains?

*The French writer Marcel Proust (1871 – 1922) wrote in the first chapter of Remembrance of Things Past …that to evoke our past by mere mental efforts is not possible. To paraphrase Proust; it seems that our memory may sometimes need assistance in the form of images or objects.

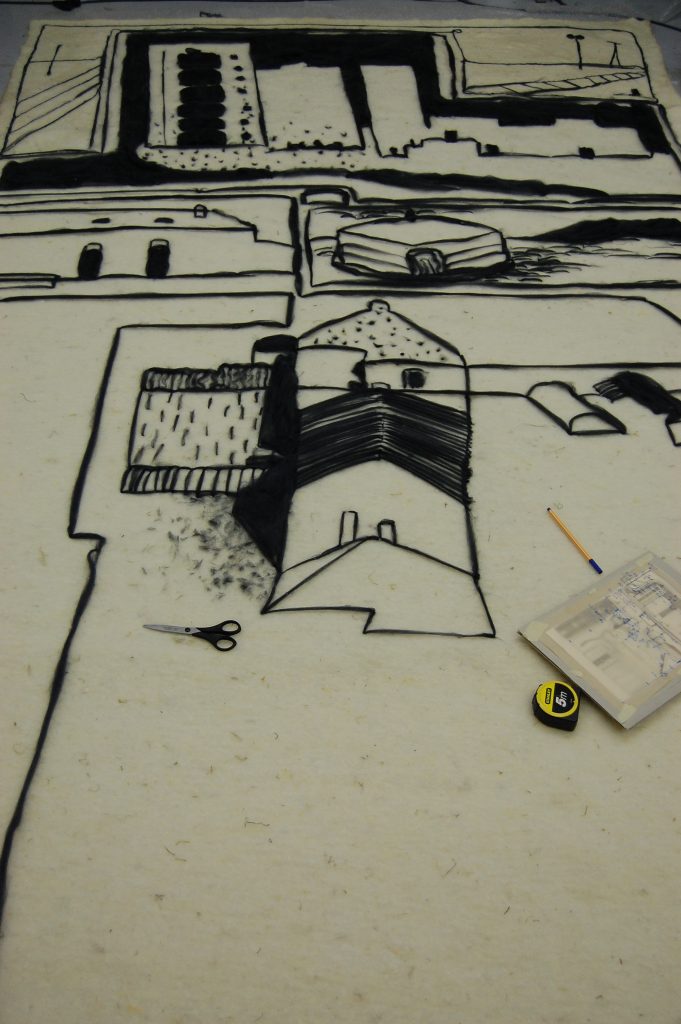

While travelling in Mongolia I discovered a fascination for felt. In Asia, felt is a common material for daily use. For quite some time Mongolia was known as “The Felt Nation” in China. Even the concept of ‘nomad’ might originate from ‘numud’, a Turkmenian name for felt. I created great tapestries out of felt with graphic drawings, illustrating views of local urban Mongolian districts. In my artwork, experimenting with different materials, forms and situations is crucial; but even more important is the dialogue with the viewer. In order to evoke a dialogue I choose the language of architecture. My sculptures, installations and drawings evoke an architectural topography. The observer should not be taken aback by inconsistencies such as an igloo or a stove made of felt. These inconsistencies create a confrontation that sets the stage to prove that life is an experiment.

What is the central image I have retained from my stay in Mongolia?

It is not the ger, the Mongolian tent, in the wide steppes or the horseman on the back of a Mongolian horse. For me it is an attraction in a plaza in the centre of Ulaanbaatar. It is a fairground with a carousel. In the background, one can read ‘Fusion’ written on an enormous billboard. For me this photo represents the gap between modernity and tradition, a nation in the state of transition.

Its counterpart is a photo I made in the autumn of 2011, in Rotterdam. The image shows a ger being set up in a plaza. The tent is meant to be an attraction for children in the neighbourhood. My partner, Bart van Lieshout, who travelled with me to Mongolia, bought the tent when we came back to Rotterdam. You can buy a ger produced in Mongolia via Internet. The ger weighs about 400 kg. You need several people to set it up. The wooden construction of the ger is covered with felt. Actually, felt is not the appropriate material for typical weather conditions in the Netherlands. Why did he push all rational thoughts to the back of his mind and buy the ger? The ger is like a flag, a national cultural symbol that mirrors the national heritage of a nation. The boundaries between cultural symbol and souvenir are fluid . Compared to souvenirs, a national cultural object can stand on its own. It does not matter in which global constellation the ger is set up. It remains a Mongolian tent. The question is how do we deal with objects of cultural value from other nations? The philosopher Francis Bacon (1561-1626) wrote a manual for travellers considering the physical as well as the immaterial souvenir:

When a traveller returneth home, let it appear that he doth not change his country manners, for those of foreign parts; but only prick in some flowers, of that he hath learned abroad, into the customs of his own country.

After the painful experiences of earlier generations, even those in the 18th century came to the conclusion that tourists are not allowed to loot foreign cities. That was the ordinance of the German ruler Franz von Anhalt-Dessau. He was fed up with visitors who took stones and plants from his palace garden as souvenirs. Actually, he knew what he was talking about; the treasure he brought home from his journeys to other parts of Europe was legendary. He himself succumbed to his yearning for souvenirs, but secretly hid the results from his contemporaries .

In my opinion, ‘Souvenir-ism’ has another meaning as well; it creates a sustainable relationship with another culture. It is like making a pact with a nation, proclaiming that you will indeed come back.